Toward Improved Quality of Life

Thomas Jefferson was unequivocal: “Without health, there is no happiness. An attention to health, then, should take the place of every other object.” During the past two decades, the association of health and quality of life has been underscored by developments that not only have meant better health for individuals but also have positioned the United States on the doorstep of transformational change in notions of good health and how it is determined. It has become clear that health is not just a matter of biology and medical care, but of behavior, of environment, and of social conditions. Along with these insights have come important new opportunities and priorities.

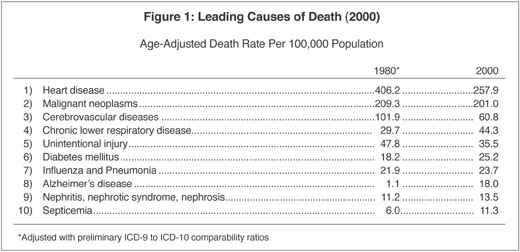

The most basic measure of progress–vital statistics records of death rates for the nation’s prominent health threats–provides a first-order indication of the trends (see figure 1). Between 1980 and 2000, age-adjusted death rates for heart disease declined by 37 percent, cancer by 4 percent, stroke by 40 percent, and injuries by 26 percent. This is good news, and it is substantially attributable to progress in prevention.

In that same period, however, some conditions have become more prevalent, with the age-adjusted death rate from diabetes increasing by 39 percent, influenza and pneumonia by 8 percent, chronic lung disease by 49 percent, kidney disease by 21 percent, and septicemia by 88 percent. The death rate from Alzheimer’s disease rose from 1.1 deaths per 100,000 people in 1980 to 18 deaths per 100,000 people in 2000. HIV/AIDS, not even known as a condition until June 1981, leapt onto the list of the 10 leading causes of death, ranking eighth at its highest rate in 1995, and then, in the face of aggressive countermeasures, dropping by 70 percent in the past six years and falling off the list. Overall, life expectancy increased by 4 years for men and 2.5 years for women, reaching 74.1 years for men and 79.5 years for women in 2000.

As life expectancy increases and population ages, issues of quality of life have become ever more compelling. There is good news on this front as well. In 2000, the proportion of people over age 65 grew to 12.6 percent, up from 11.3 percent in 1980, and is expected to reach 20 percent by 2030. Yet, as the population ages, disability among older people is declining. Mortality dropped by about 1 percent per year among older people during the past two decades, and disability rates declined even more, by about 2 percent per year. The proportion of older people living in institutions declined to 4.2 percent in 1999 from 6.8 percent in 1982.

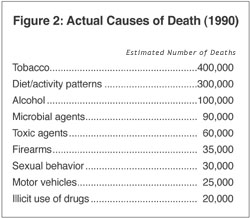

In part, these improvements have come about because of greater appreciation of controllable risks and more efforts to reduce those risks. Research, some of which began a half century ago, has gradually deepened our understanding of the etiologic factors underlying the most common sources of disease and disability. Studies of the relative contributions of various factors to the leading health threats suggest that actual leading causes of death in 1990 were not heart disease and cancer, but tobacco and the combination of sedentary lifestyles and unhealthy diets. More recent assessments indicate that tobacco has now been overtaken by diet and inactivity as the leading threat to health.

Insights of the past two decades have provided a much better appreciation of the fact that conditions such as heart disease, cancer, stroke, diabetes, and even injuries are essentially the pathophysiologic endpoints of a complex interplay of an individual’s experiences in five domains of influence: genetic predisposition, social circumstance, physical environment, behavior, and medical care. The finding that 40 percent of premature mortality is attributable to behavioral factors even provides the beginning of a quantitative sense of the relative contributions of these domains (see figure 2).

But the important issue is not how much risk is contributed by each factor, because the factors do not act independently. The key dynamics determining health occur at the intersections of the various domains of influence: how they interface to shape a person’s fate. This is the particularly exciting dimension of the years ahead: learning how these factors interact with each person’s predispositions to shape his or her own health futures, and how the factors might be controlled to improve that person’s prospects.

Much has been learned about these predispositions, as progress in genetics sets the stage for broader progress in prevention. With the sequencing of the 3 billion base pairs in the human genome now complete, work to elucidate the structure and function of the genome’s 30,000 to 40,000 genes is proceeding apace. As this work unfolds, it will be possible to place genetic instructions into the experimental contexts within which they are expressed, and target with greater specificity interventions for groups and individuals. Greater clarity of insights into the interrelationship among factors will provide greater clarity to our challenges and opportunities. Environmental exposures and behavioral patterns may determine whether a gene is expressed. Social circumstances affect the nature and consequences of a person’s behavioral choices. Genetic predispositions affect the health care that people need, and social circumstances affect the health care they receive.

Even before we learn more about the ways things work, we have many available opportunities for further gains from prevention. Despite current knowledge about the importance of behavioral contributions to illness and injury, some 127 million adults in the United States are obese or overweight, 47 million still smoke, 17 million are diabetic, 14 million abuse alcohol, and 16 million use addictive drugs. Approximately 900,000 people are still infected with HIV, and last year some 900,000 teens became pregnant. The burden of conditions preventable by behavior change alone is substantial.

There also are many opportunities for medical care to do better in preventing disease. Nearly one in five children remains inadequately immunized against the major childhood vaccine-preventable diseases. An estimated four out of five people with high blood pressure lack adequate treatment, as do as many as a quarter of those with elevated cholesterol levels. Approximately 30 percent of women do not receive mammograms, and 20 percent do not receive cervical screening. Fewer than 40 percent of adults who are 50 and older have been screened for colorectal cancer in the past two years. Fewer than 20 percent of smokers receive cessation counseling or treatment. With health care commanding 15 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product, the medical care system misses very few opportunities to treat disease after it occurs, yet daily misses countless opportunities for prevention.

National health agenda

When it comes to prevention, medical care should have lots of allies lining up to play a role. People who exercise have lower rates of premature death, chronic disease, stress-related disorders, and instability during old age. Dietary interventions can reduce obesity, as well as heart attacks, stroke, diabetes, and certain cancers. Yet fewer than a quarter of employer-sponsored health plans offer any kind of smoking-cessation service, and fewer than a third offer counseling for nutrition or physical activity.

To accelerate progress through stronger focus, Healthy People 2010, a national health agenda prepared by scientists within and outside the federal government, presented a set of leading health indicators representing the conditions with the greatest potential to shape the nation’s health over the decade ahead.

For each health indicator, the challenge is considerable, but so is the possibility of progress, given today’s knowledge base. If the possible is captured, then the nation should anticipate a healthy 21st century, in which:

- The right start is given to every child, with nurturing relationships that can help protect each one from harm.

- The opportunity for lifelong vitality is available to every individual and derives from the power of health-promoting behaviors.

- The environment is safe, nurturing, supportive of healthy lifestyles, and free of unusual hazards.

- No addicted person goes untreated.

- Medical care is of high quality, and no person goes without the prevention and treatment services that have been proved effective for his or her needs.

- We live in a caring society, one in which those who are isolated or estranged will not suffer illness or injury as a result of society’s neglect.

- We have the comfort and choices necessary for a humane conclusion to our lives.

The United States is at the threshold of a period of unique opportunity, a time in which, as the saying goes, people will be able to focus not just on adding years to their lives, but on adding life to their years. Given the knowledge and resources already in hand, the elements of this vision are all possible–if all segments of society can marshal the will. This is the mandate for the nation’s prevention agenda.